Cloud computing infrastructure has become the default foundation for modern products, but “moving to the cloud” is not the same as being ready to scale. Teams often discover the hard way that what worked for an MVP (a single account, a flat network, a few manually created resources) becomes fragile, expensive, and risky as usage grows.

Designing cloud infrastructure for scale and security means treating it like a product: architected with clear boundaries, automated change control, continuous verification, and measurable operational outcomes.

What “cloud computing infrastructure” actually includes

When people say “infrastructure”, they often mean compute and networking. In practice, cloud computing infrastructure is a full system that spans:

- Identity and access (human and machine authentication, authorisation, audit)

- Network foundations (segmentation, egress control, private connectivity, DNS)

- Compute platforms (VMs, managed Kubernetes, serverless)

- Data services (databases, object storage, queues, caches)

- Security controls (logging, vulnerability management, key management, policy)

- Delivery and change management (CI/CD, Infrastructure as Code, approvals)

- Observability and operations (metrics, logs, traces, alerting, incident response)

If you want infrastructure that scales without turning into chaos, you need consistent patterns across all these layers, not just “more instances”.

Design for scale: the patterns that keep working as you grow

Scaling is not only a capacity problem. It is also a dependency and failure-mode problem. The goal is to make growth boring: predictable behaviour under load, predictable recovery when things go wrong, and predictable costs.

1) Start with workload “shape”, then pick compute

A simple but effective starting point:

- Steady, long-running services: containers on managed Kubernetes (or managed PaaS) tend to be easier to operate at scale than fleets of bespoke VMs.

- Spiky or event-driven workloads: serverless or queue-based workers often provide better elasticity with fewer scaling knobs.

- Stateful systems: prefer managed database services where possible, then scale stateless tiers around them.

What matters most is reducing your “operational surface area”. Managed services are not always the right answer, but they often eliminate entire classes of scaling and patching work.

2) Build for horizontal scale and graceful degradation

Horizontal scale works best when services are stateless or keep state externalised (databases, object stores, caches). Where state is unavoidable, isolate it and harden it.

Two practices that consistently pay off:

- Decouple with queues and events so your system can absorb bursts without melting core dependencies.

- Limit blast radius (for example with per-service rate limits, circuit breakers, and bulkheads) so one hotspot does not take down the whole platform.

To make these choices more concrete, here is a quick reference you can use in design reviews:

| Scaling need | Reliable infrastructure pattern | Why it helps | Common mistake to avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sudden traffic spikes | Autoscaling behind load balancers | Adds capacity with minimal operator action | Scaling only the web tier while DB is the bottleneck |

| Slow downstream dependency | Queue + worker pool | Protects user-facing latency, enables backpressure | Unbounded queues with no DLQ and no alerts |

| Global users | CDN + edge caching | Reduces latency and origin load | Serving all content from one region |

| High availability | Multi-AZ, health checks, self-healing | Survives common infrastructure failures | “Active-active” without data consistency plan |

| High write throughput | Partitioning and write optimisation | Keeps data layer stable under growth | Over-sharding too early without clear access patterns |

A useful mental model here is to design like an SRE: define what “good” looks like (availability and latency targets), then engineer the platform to hit those targets under expected failure scenarios. The Google SRE book remains a solid foundation for this way of thinking.

3) Use multi-AZ by default, treat multi-region as a business decision

In most mainstream cloud platforms, multi-AZ deployment is the baseline for production workloads. It protects against many common failures and typically has a manageable complexity cost.

Multi-region is different. It can be the right move for regulatory, latency, or resilience reasons, but it introduces real complexity (data replication, failover orchestration, routing, testing). Decide multi-region based on RTO/RPO and user impact, not as a generic best practice.

4) Scale includes your delivery system

Teams focus on autoscaling infrastructure but forget the delivery pipeline. At higher change velocity, your bottleneck becomes:

- manual environment creation

- inconsistent configurations between environments

- brittle deployment steps

- emergency fixes applied directly in production

Infrastructure that scales is infrastructure that is reproducible. That typically means Infrastructure as Code plus a controlled promotion path (dev to staging to production) with automated checks.

For cloud architecture guidance that aligns scaling decisions to reliability and operational excellence, the AWS Well-Architected Framework is a widely used reference, even if you are not fully AWS-native.

Design for security: make controls part of the platform, not a ticket queue

Security at scale fails when it depends on human memory. Secure cloud computing infrastructure makes the safe path the easiest path.

1) Anchor security in the shared responsibility model

Cloud providers secure the underlying facilities and many service components, but you still own:

- identity and access policies

- network exposure

- data classification and handling

- workload configuration and patching responsibilities (depending on service type)

- logging, detection, and response

If you treat security as “provider handles it”, you end up with preventable misconfigurations.

2) Identity-first security (and strong separation of duties)

In modern cloud environments, most serious incidents are rooted in identity misuse: overly broad permissions, leaked keys, weak authentication, and lack of auditability.

A strong baseline includes:

- centralised SSO and MFA for humans

- short-lived credentials for machines (avoid long-lived access keys where possible)

- least privilege with role-based access and clear ownership

- separate environments (and ideally separate accounts/projects/subscriptions) to reduce blast radius

For organisations building an evidence-driven security programme, mapping controls to NIST SP 800-53 is a common approach, even when you are not in the US public sector.

3) Network segmentation and egress control

Flat networks scale poorly for security. As your estate grows, you need clear boundaries:

- separate public ingress from private workloads

- isolate sensitive data systems

- control outbound traffic (egress) to reduce exfiltration risk

This is also where “security meets cost”: unmanaged egress can become a major spend driver, and visibility here supports both security and FinOps.

4) Secure-by-default build and deployment

If your CI/CD pipeline can deploy infrastructure, it can also enforce security and compliance checks automatically. Examples include:

- policy-as-code checks before provisioning

- image scanning and SBOM generation

- secrets scanning and approval gates for risky changes

The CIS Benchmarks are a widely used baseline for hardening cloud services and operating systems, and they translate well into automated checks.

To show what “security as part of the platform” looks like, here is a practical control map you can adapt:

| Security domain | Minimum baseline for production | How to automate it |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | SSO + MFA, least privilege roles, break-glass accounts | IAM templates, access reviews, guardrails/policies |

| Data protection | Encryption in transit and at rest, key management | KMS policies, TLS enforcement, automated rotation |

| Workload security | Hardened images, vulnerability scanning, runtime controls | CI scanning, admission policies, continuous patching |

| Logging and audit | Centralised logs, immutable audit trail, alerting | Log pipelines, SIEM integration, detection-as-code |

| Network security | Segmentation, WAF where relevant, egress control | IaC network modules, firewall policies, continuous drift detection |

| Resilience | Backups, tested restore, defined RTO/RPO | Backup automation, DR runbooks, scheduled recovery tests |

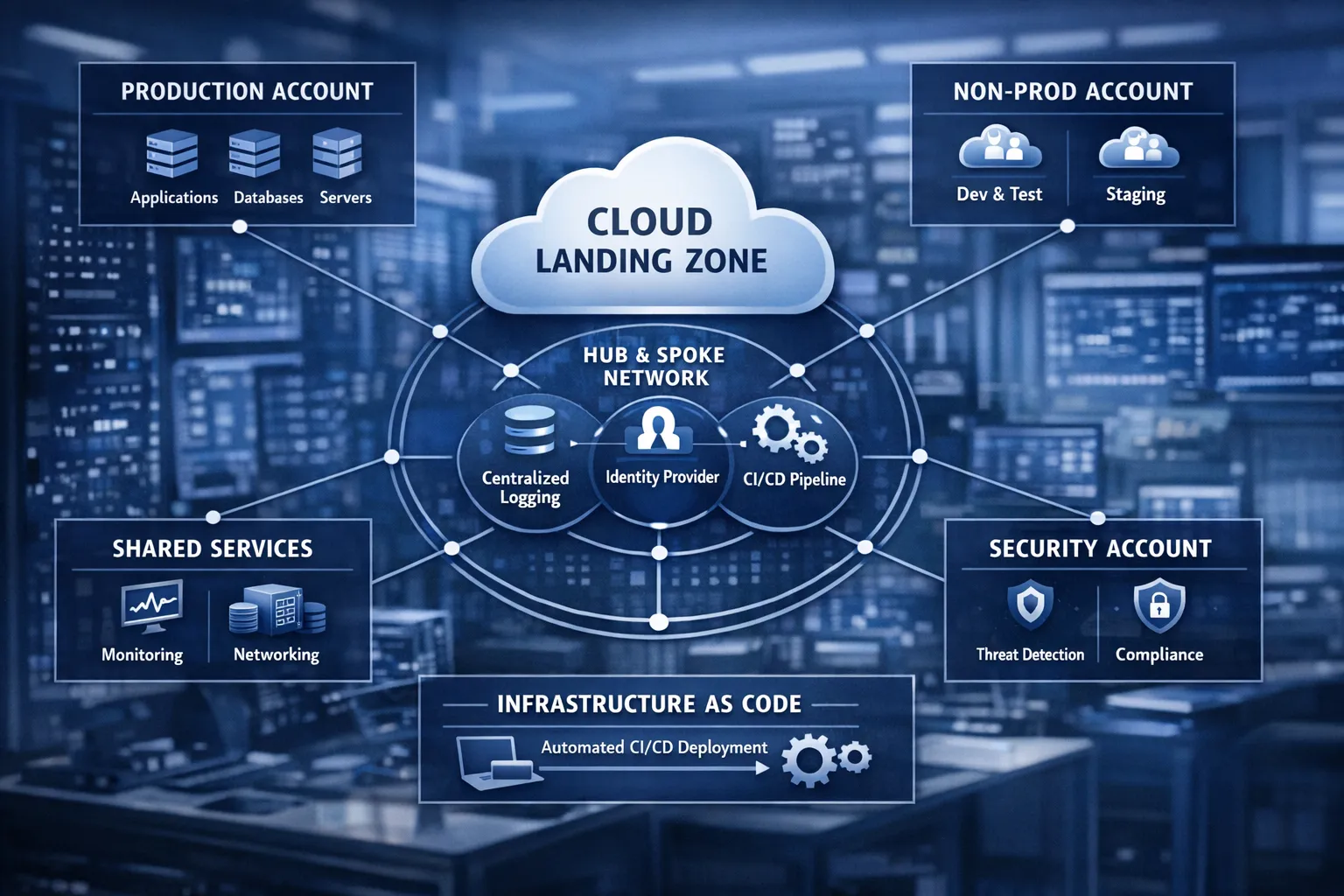

A scalable and secure reference blueprint (landing zone thinking)

Most scaling and security failures trace back to weak foundations. A “landing zone” is simply a structured cloud foundation that standardises identity, networking, security controls, and environment separation before teams ship dozens of workloads.

A practical reference blueprint usually includes:

- Multi-account or multi-project structure: separate production, non-production, shared services, and security tooling

- Standard network layout: clear ingress, private subnets, controlled egress, private endpoints where appropriate

- Centralised logging and security monitoring: logs flow to a dedicated security account/workspace with restricted access

- Infrastructure modules: versioned building blocks for networks, clusters, databases, and observability

- Guardrails: policy-as-code for “things you must not do” (for example public buckets, wide-open security groups)

- Golden paths: paved, supported ways for teams to deploy services safely

If you want to keep up with evolving patterns across AWS, Azure, migrations, and compliance topics, a curated hub like these cloud computing articles and resources can be useful for ongoing education and internal enablement.

Operating the platform: reliability, response, and cost control

Great infrastructure design is only “great” if it survives real operations. As platforms scale, the operational model often determines whether teams ship faster or drown in incidents.

Observability that supports action

At scale, you cannot debug by logging into servers. Aim for:

- meaningful service-level indicators (latency, error rate, saturation)

- correlation across metrics, logs, and traces (often via OpenTelemetry)

- alerting on symptoms tied to user impact, not just resource thresholds

If you are building a modern telemetry strategy, the OpenTelemetry project is now a mainstream standard for vendor-neutral instrumentation.

Resilience and recovery as a routine practice

Backups are not a resilience strategy unless restores are tested. Similarly, a DR plan that has never been executed is a document, not a capability.

Resilience practices that scale well include:

- regular recovery tests in non-production

- well-defined RTO/RPO targets per service

- runbooks that are short, decision-oriented, and actually used in incidents

FinOps as a design constraint, not a quarterly surprise

Cloud cost is an engineering output. The most reliable cost control mechanisms are designed into infrastructure:

- tagging and cost allocation standards

- budgets and anomaly detection

- autoscaling that scales down as well as up

- right-sizing as part of regular operational hygiene

Cost governance also strengthens security, because it forces visibility into “what exists” and “who owns it”.

The most common failure modes (and what to do instead)

Even mature teams repeat a few predictable mistakes. If you want a quick self-check, look for these patterns:

Manual changes in production

If operators regularly “just fix it in the console”, you will accumulate configuration drift and lose auditability.

A better approach is to make Infrastructure as Code the source of truth, then enforce it with drift detection and controlled promotion.

Over-permissive IAM to move fast

Teams often start with broad permissions, then never reduce them. This becomes high-risk as the environment grows.

Instead, create role templates aligned to job functions, enforce least privilege, and centralise audit logs so access is reviewable.

Flat networks and default exposure

A single shared network with ad-hoc rules becomes unmanageable. Worse, one misconfiguration can expose sensitive workloads.

Instead, segment early, standardise ingress patterns, and control egress.

Scaling the app without scaling the data layer

Many incidents look like “we need more pods”, but the true bottleneck is database connections, locking, or unoptimised queries.

Instead, include data scaling in the architecture and load testing, and design backpressure patterns (queues, caching, rate limiting).

Where Tasrie IT Services can help

If you are redesigning cloud computing infrastructure for scale and security, the biggest accelerators are usually:

- an architecture assessment that identifies bottlenecks and high-risk failure modes

- a secure foundation (landing zone) with guardrails and reproducible environments

- Infrastructure as Code and CI/CD automation for consistent change control

- observability, incident readiness, and resilience testing embedded into operations

Tasrie IT Services provides DevOps, cloud native, Kubernetes, automation, and cybersecurity consulting with a focus on measurable outcomes and senior engineering delivery. If you need a second opinion on your current design, or want help implementing a scalable and secure foundation, you can start with a structured assessment and an execution plan that fits your team and constraints.